Our recommendations for the top CBA issues

October 14, 2012 Leave a Comment

Everyone has their opinion about what the final agreement should look. Here are our two cents based on finding some type of balance for both sides and addressing the major issues from both an economic and sustainability perspective.

Revenue Share:

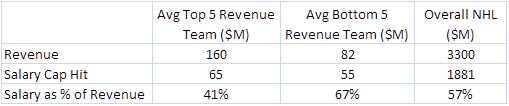

Our recommendation is to have the revenue share start at 53% for the players in 2012/13 and be reduced by 1% each year until it reaches 50/50 in 2015/16. At the same time, all currently signed contracts should be paid without an across-the-board reduction. However, we also suggest for salary cap purposes, all current contracts be prorated for the salary (e.g. only count at 93% against the cap in Year 1 – 53% divided by 57%) based on the current year rev share percentage divided by 57%. As a result, all current contracts would still be paid at the full amount, but allow teams to manage the salary cap in a more reasonable manner. Thus teams with large long-term contracts will be ‘punished’ by having to pay the full cash amount but not be harmed from a salary cap perspective.

Contract Lengths:

As mentioned previously, 10 years is too long and does not make economic sense for a contract length given the lack of visibility into any contract 10 years out. We recommend a maximum of 7 years for UFAs and 5 years for players who are RFAs.

HRR :

This is a very complicated issue as Elliotte Friedman has pointed out. It seems like the current CBA has flaws, in particular because the agreement tried to simplify things across all 30 teams by setting rules to simplify the effort required to calculate true HRR. If the NHL & NHLPA agree not make any changes to HRR that is fine – but in reality all revenue related to hockey players performing on the ice should be included with the owners calculations with direct costs being subtracted to determine the net shareable revenue.

Clearly there were many challenges in the recently expired CBA, at the team level that created unintended consequences and need to be addressed. I would suggest spending a little more money and time to get an impartial cost-accounting expert/firm to develop an activity based costing approach for each of the 30 teams that can be updated every year based that adjusts to the dynamics of each team/arena. This would address head-on all the nuances of owning/operating versus not owning the arena handle both revenue and costs in a more accurate manner to reflect actual hockey-related activity.

Cost Sharing:

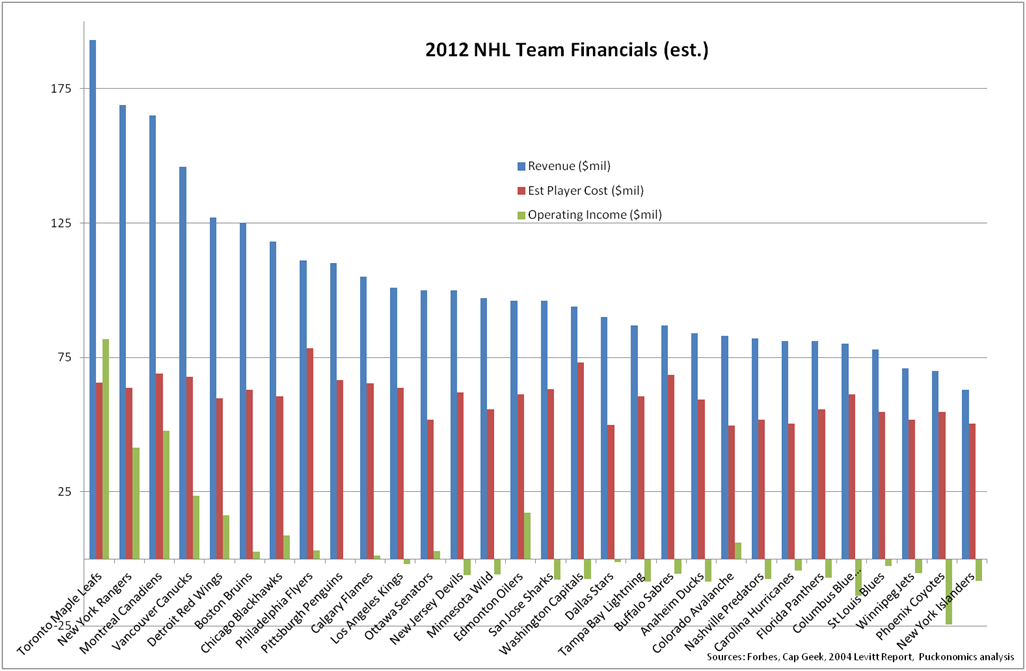

We recommend the NHL adopts cost sharing, not revenue sharing, for the top 5 revenue generating teams to offset the player and travel costs for the bottom 5 revenue generating teams for games in which the low-revenue team visits the high-revenue team.